Time to sort the wheat from the chaff

Share

THOUGHT LEADERSHIP BY CRAIG SWANGER

This age-old farming expression applies perfectly to today’s market conditions. As markets shift rapidly from “greed” to “fear”, fundamentals (the wheat) get mixed up with a lot irrational fears (the chaff).

Experienced investors will look past these irrational fears for where the real risks are, but as the cycle goes on, more importantly look for oversold assets before the next greed cycle starts.

The irrational oversold fear at the moment is the impact of rampant inflation on equities, bonds and property assets. This article dives into why we believe that some markets have over-reacted and will soon bounce back.

Inflation: Will be less than markets are pricing in

Markets tend to suffer from group-think. When buying or selling pressure mounts, most market participants simply follow each other as they don’t have sufficient conviction in any contrarian views they might hold. Market-leading investors however will question this group-think not to be argumentative, but to find opportunities to profit from the market over-reacting.

The current sell-off in global equities and other risky assets is caused by the fear of inflation. Most of the market is now pricing in inflation to remain uncertain for several years, so they have sold any assets that could suffer a fall in earnings at the hands of high inflation.

But the reality is that the causes of inflation at the moment are both transitionary and predictable. This is not a return to the 1970s when inflation got away from central banks.

In turn that means that the factors that markets have so aggressively priced in over the past few months will soon surprise markets with how short-lived they are. Inflation will hold at these very high levels, but only until mid-2023. More importantly for property and bond markets, interest rates will spike sharply in 2022, but then very quickly fall back to the new neutral levels.

Fundamentals: This is not the 1970s

Looking past all of the fear commentary to the rational truths about today’s global economy, it is plainly evident that it is not now nor will it be again, the 1970s:

-

Leverage: 0.25% increase in rates today is the same as 0.75% increase in the 1990s

This is the number one reason that markets’ concerns about interest rates increasing by 2-3% in the US, UK, EU, Japan and Australia. Interest rates will only rise if central banks choose them too, or if markets assume that the central banks will do so. Central banks’ mandate is to keep inflation in a target range and/or maximise employment. So central banks will not increase or leave interest rates high for any longer than needed to curb inflation. In particular, even if they need to cause a recession to curb inflation, they will err on the side of inflation rather than risk creating economic collapse.

Here's where leverage in the economy is vital to understand when predicting interest rates. Every economy has a particular sector that is more leveraged than the rest. Which sector that is will depend upon taxation policy and financial market maturity usually; for example, in Australia negative gearing and an investment bias toward residential property means that the household sector is the most leveraged. In the US, EU and Japan where access to capital is strong due to very high household savings, the government sector is the most leveraged. And in China, where centrally controlled funding of corporate debt is the dominant feature of economic management, corporate debt is the highest point of leverage.

It doesn’t matter which sector is the most leveraged. What matters is how much of an increase in rates can that sector cop with before there is a severe downturn in their spending. That will define how far central banks will go as it defines the break point for that economy.

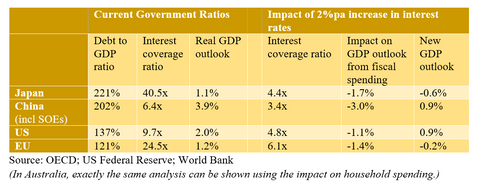

Using the US, Japan and the EU as an illustration of why interest rates simply cannot rise as much as previous cycles, the table below shows that a long-term increase in rates of 2%pa would send many of these economies into a permanent recession and practically erase global growth.

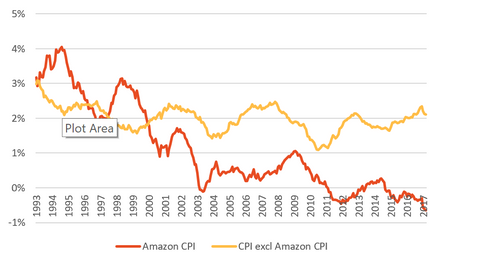

- Distribution technology: The dominant cause of low inflation since around 2000 has been the digital economic revolution. Stoic’s analysis shown below indicates that digital technology had an average deflationary impact of 0.75%pa leading up to the pandemic, increasing as the proportion of goods and services purchased online increased (as shown in the blue chart line below). There is no rationale for expecting this trend to end with the pandemic.

“Amazon Inflation Index”

US CPI split into goods and services mostly traded online vs the rest

- Labour markets: Unionised labour is now 65% lower than the 1970s (OECD). Unions bargaining power in the 1970s allowed them to win wage increases in excess of inflation, which in turn pushed up inflation further, creating more wage demands and so the spiral went upwards. Unions now have less than 20% control over labour inputs in the OECD other than Scandinavia. This means that the 1970s self-spiralling nexus between inflation and wages is highly unlikely to be repeated.

- Flexibility of the supply chain: China’s extraordinary economic awakening has expotentially increased the global supply chain’s flexibility to respond to market forces. The current impact of the closure of some of the world’s ports is a transitionary impact as there is no possibility of China letting the economic impact of these closures risking social unrest, a tipping point that is inevitable but with China’s mastery of centralised control, unlikely. The supply chain in the 1970s was subject to shocks, particularly in the oil prices, due to large inventory stockpiles and far narrower range of sources of supply.

What does this mean for investors?

Consider these factors the “wheat”. The market’s headlines, pushed by a lazy and sensationalist business media are the “chaff”. Its up to you of course, but any successful farmer for the past thousand years will tell you where the smart money will go.

Investment markets are right to punish companies with thin profit margins and subject to pricing pressures, such as the consumer discretionary sector or farming. But the sell-off in small caps and technology in particular is purely an irrational flight away from all risk. These sell-offs always end the same way: a rebound based on fundamentals, and profits for those that get set first.